This post started as a podcast, but then I realized it’s

much easier to “see” than to hear. I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about

inciting incidents as I work through my arc workshop. You figure I’d have

organized it before now. Holding my thoughts up to things to see if they work

the way I think they do. Sometimes you think you’ve found something that “always”

works the same way, but doesn’t.

Back in the early days, when I’d just started to write

seriously and didn’t have any idea what the difference was between a scene and

a turning point, people used to talk to me about inciting incidents, and I

totally had no clue. I’d just nod and go along pretending like I knew what they

were talking about, which is a good thing in retrospect, because everyone had

their own idea of what an inciting incident is:

It’s something in

backstory:

The heroine decides to go to a Sasquatch conference in the

wilds of northern WA

It’s how you start

your story:

Maybe she breaks down on the side of the road

Or it’s something

wild and dramatic that happens when the two protags get together:

A hot and hunky cowboy/xenobiologist rescues her and takes

her off to his lair

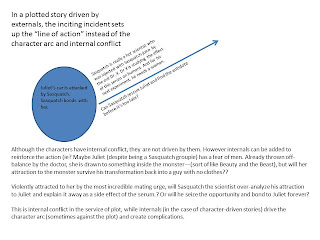

I think there are two “kinds” of inciting incidents. One for

externally-driven stories—plotted stories that are pushed along by things

outside character, like romantic suspense and thrillers. And another for character-driven

stories like contemporaries or mainstream fiction, where they’re driven by

internal conflict.

An example for purposes of this post is Kim, because her

story is a fairly straightforward contemporary romance.

Kim is a shutdown widow who lost her child in a horribly

traumatic accident. As the story starts, the toilet in her bed and breakfast

breaks and she calls Jason, a handyman who just moved in down the street. At

the end of the day, Jason invites her to dinner at his place.

So far, the sequence of story events is:

·

(backstory)

·

Kim loses her husband to a heart attack

·

Goes through a red light while grieving and her

daughter, Cleo, is killed

·

Decides to fix the bed and breakfast because she

can’t let go

·

(the story, two years later)

·

She’s getting ready for a soft opening (it’s

coming up on Cleo’s birthday and the anniversary of her death. Kim isn’t in

good shape)

·

The toilet breaks (pushing her closer to her

already fragile edge)

·

She calls the handyman down the street (he

posted flyers everywhere when he moved in)

·

He fixes the toilet and over the course of the

day gets to know her a little (she looks like she’s hurting and could use a

meal)

·

He asks her over to dinner with him and his kid

Although Cleo’s death is a major issue and drives Kim’s

conflict as she falls in love with Jason, the inciting incident in Kim’s story

isn’t in backstory because there are too many branching points. In other words,

Cleo’s death doesn’t limit the story—it can be anything from a romantic suspense,

paranormal to a dimension hopping sci-fi opus.

Backstory like Cleo’s death is simply stuff your reader

needs to know to understand what’s at stake. Can we really cheer someone on if

the only thing we know about her is her frustration over a plugged toilet? By

the time the inciting incident happens we should know Kim suffered a tragedy

and she’s working on the bed & breakfast because she can’t let go of her ghosts.

She wants to make amends and can’t. Survivors guilt, nightmares, and regrets

are eating her alive. The line of action (can Kim open the bed and breakfast in

time to take advantage of a festival in town?) is very simple, which allows

what’s happening up in Kim’s head to shine. Which means in this instance, what

starts the story also isn’t the inciting incident, because the story isn’t

limited by Kim’s decision to open a bed and breakfast, although the

possibilities are starting to get narrower.

In a story driven by

internals, exposition narrows the story down to a bunch of manageable

probabilities at the same time it shows us the stakes and creates reader buy-in.

Starting too close to the inciting incident means the story

runs the risk that the reader won’t understand what the story is really about (the

story question).

On the surface, the story is all about Kim making her bed

and breakfast a success. Internally, it’s all about self-forgiveness, letting

go and second chances. Which means the story question is whether Kim can let go

of the past, forgive herself and take her second chance at love and family.

Her daughter died, and she shut herself down emotionally.

Can she ever open up to love again? We’ve seen her all alone in her extra-large

house. If something can’t break down the walls she’s built around herself, Kim

will be alone forever, hating herself more with every passing day. Which means

the inciting incident is Jason’s invitation to dinner. His invitation does two

things:

It sets up the parameters of the story—Jason is a handyman

and single dad, with a cute kid. They all live in a small town. There’s nothing

paranormal about the story, and there are no thriller or mystery elements. It’s

a simple, plain vanilla relationship story defined by the question: Can Kim let

go of the past, forgive herself and take her second chance at love and family?

The story either starts or stops here—if Kim doesn’t say yes,

the story where Kim and Jason struggle over the growth of their relationship

wouldn’t happen because they’d still be two people who just happen to be in a

story together and there’s nothing much going on.

The inciting incident (what it’s about and where it falls) foreshadows

the structure (plot-driven or

character-driven) by defining what’s important to the story.

Even though my sasquatch-loving heroine has been rescued by

the xenobiologist-cowboy, the incident doesn’t set up the story or create a

stopping or starting point, which means at the point Dr. X rescues fair Juliet,

they’re still two random people in a story and the story is still working

through the expositionary phase. It’s character-driven and we’re waiting to

find out what’s going on between Dr. X and Juliet because the inciting incident

hasn’t happened yet.

However, if I had Sasquatch smash Juliet’s car into scrap

metal and fall madly in love (maybe some of that instant mating stuff?) with

her, only to have Dr. X rescue Juliet—keeping her safe one step ahead of the

hero who X transformed into a horrible Sasquatch, then it’s a race against time

and Dr. X to rescue Juliet before the dastardly villain can turn her into

She-squatch and find the antidote so the hero can be revealed as the piping hot

hero he really is.

While Juliet, Dr. X and Sasquatch are all strong characters,

the story they’re in is plot-driven, and the inciting incident (Sasquatch

bonding with Juliet only to have her kidnapped by the evil Dr. X) is right up

front (or very close to the front) to emphasize what the story is about (will

the hero rescue Juliet before she’s turned into a female monster, and can they

find the antidote to turn the hero back into a human, before it’s too late?).

2 comments:

I love how clearly you explain such difficult concepts Jodi. As I begin my wip I have the heroine and hero meeting up again after a long time. The inciting incident doesn't occur until the beginning of chapter 2. My biggest challenge is filling in the back story without creating an information dump. It's a case of picking and choosing the details relevant and necessary for understanding the plot while setting up expectations for the characters' developmental / transformational arcs. I'll keep at it until I get it right! :0

Edith, I have faith you'll get it. And I sincerely admire your dedication. :)

Post a Comment