I came across this powerpoint yesterday while I was cleaning

out a workshop and fell in love with it all over again. I guess this is where I

admit I fall in love with most of my powerpoints, lol. They’re just so…shiny.

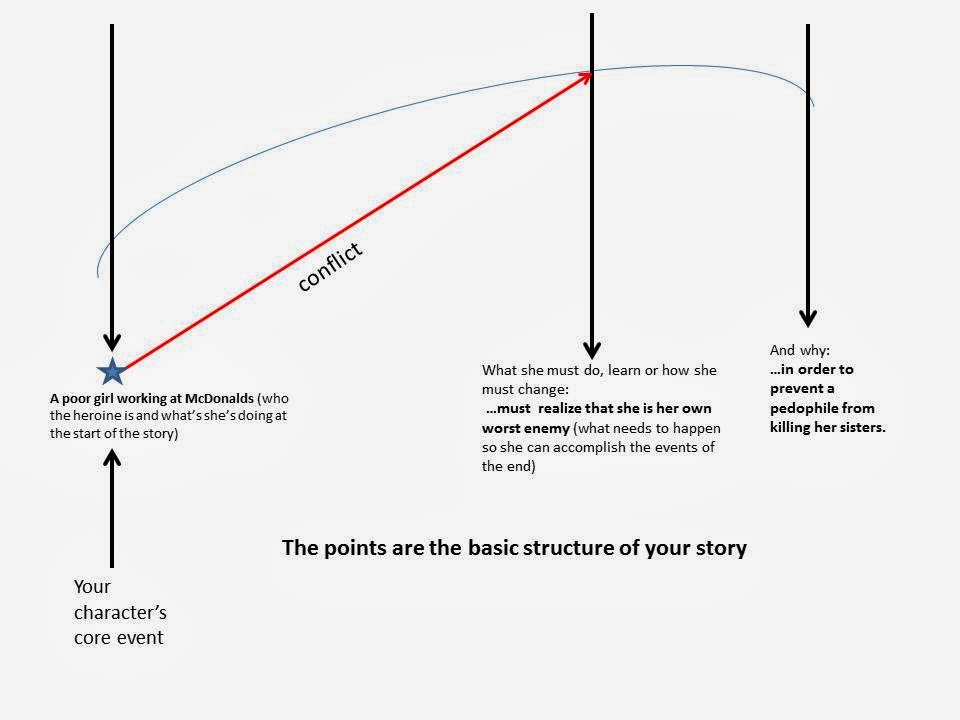

This is a schematic I did back when I was solidifying my

thoughts on the arc and how it worked. Until I sat there and took a good, hard

look, I’d always bought into the whole stages and steps things, but the more

study I did into how the arc worked in real-life wips, the simpler I realized

it really was. You can’t impose structure on everything if everything is…well, “everything.”

Some people write huge convoluted things, and some don’t. Which means that any

structure big enough to encompass everything needs to be fairly spare.

I always tell people you can scale up and scale down, adding

more stages and steps if it works for your comfort level, or strip it down, if

you’re comfortable using three points. Sort of like boats, you know? Some people

love all that GPS and computerized stuff, and some are just as comfortable with

a sextant and the stars.

Every character starts out at pt A, with some kind of

backstory pertinent to the story. And lol!!! Trying to say this cold, not in

the context of a workshop just stopped me, so let’s talk about “backstory

pertinent to a story”.

What is pertinent

backstory and how is it different from “backstory” in general?

Every character has backstory, because everyone has a past. However,

everything in a character’s backstory doesn’t always work for a story. The fact

that I really like Hostess Raspberry Zingers has no bearing on anything 99.9

percent of the time. I’m not sure what it was that caused me to side with

raspberry-coconut instead of chocolate or twinkies, but it only impacts a story

where I’m picking out a snack.

So let’s go back to that statement>

Every character has backstory, because everyone has a past.

Yeah, everyone has a past, but if you don’t narrow it down

to what’s going to drive your character through the story, how will you know

what they’ll do? If I just say Mercedes is this poor kid who works at MacDonald’s

and her sisters were just kidnapped, how will I know Mercedes will fight tooth

and nail to get her sisters back, regardless of how many issues she has? I can’t

give her motivation simply because I say she has motivation. Motivation, along

with conflict, comes from the inside, and that’s where core events come in.

While it might be sort of a cheat to say to that every character

contains a core event in relation to their story, characters need a handle—some

way to work with a character that doesn’t squash them flat and allows them to

grow and change.

One thing I’ve gotten a lot firmer on over the years is the

difference between contemporaries and stories with a heavy dose of external

events, like paranormals, romantic suspense, mysteries and thrillers. I usually

use Kim’s story to talk about emotional structure and Mercedes to talk about

the transformational arc, because they’re vastly different stories. Kim’s

story, being a contemporary, has no big external story arc. Kim needs to open

her bed and breakfast on time, but if push comes to shove, she can do it

without a bathroom in the bridal suite. Mercedes’s story, being a romantic

suspense, has a huge, fast-running external arc. She “needs” to find her sisters

before the villain kills them which means the space between pt A (the way she

starts out) and pt B (her transformational point) is full of scenes that

address three things. The externals (rescuing her sisters), her arc (she needs to stop holding

herself down or she’ll never change in time to rescue the twins) and her

relationship with the hero (since this is a romance). These three things

flip-flop around, depending on what you’re writing. If you’re writing a

mystery, the scenes need to address solving the mystery and the protagonist’s

arc, but not necessarily a relationship of some sort. “However” if it’s a contemporary,

the scenes should address Kim’s transformational arc and her relationship with

Jason, although not necessarily Kim’s battle to fix up the bed and breakfast.

One thing all stories have is theme, or some way to keep the

scenes on the straight and narrow, and that’s pretty much in every story—but it’s

something to talk about another day.

1 comment:

"Motivation, along with conflict, comes from the inside, and that’s where core events come in."

Oh, this is HUGE.

It means that the motivation is going to play out in the internal arc, and THAT's how the internal arc affects the external arc.

There really is no way to have a *good* character-driven story without those two arcs being developed on the page for the reader. If we don't get the internal arc right, the reader is going to find it hard to suspend disbelief when a character's actions affect the external plot.

And so if we need a character to behave in a certain way, then we need to choose the core event in their backstory that will bring about the most conflict for them. And the conflict is going to ultimately lead them to change (hopefully) and grow into an even better version of themselves.

Feeling in a bit of a philosophical mood just now, I'd say that all this doesn't necessarily remain within the pages of a novel. It could also apply to real life too! :)

Post a Comment